As I pursue a career in digital journalism, there’s no choice but to prepare myself for the dynamic evolution of emerging technologies and how they will change the way we tell and share stories.

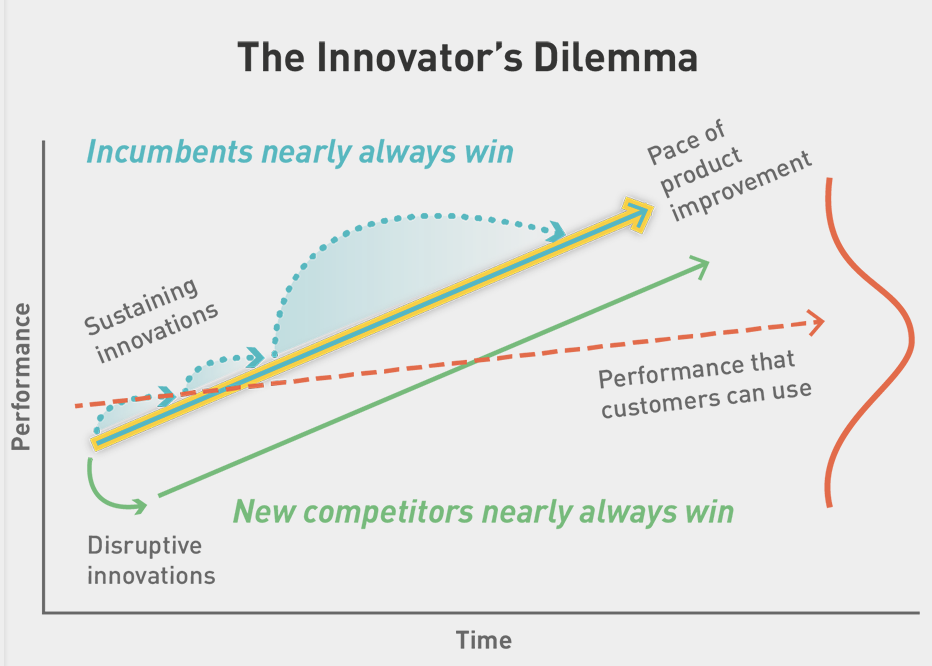

Over the next several decades I can imagine that independent publishers will continue to struggle. The overtake of streaming content, pivot to video, and acquisition of small newsrooms will force publishers to reconsider their business models and ability to hire young professional writers.

But, we can also be hopeful for the benefits of new tech that will make publishing easier, faster and more immersive. Anyone can already have a website or blog, and now that more people are becoming adept at visual media creation, anyone can publish complete story packages from their personal mobile devices.

This isn’t really new or unexpected. But this class has taught me to look past where storytellers are currently pushing the envelope, and into an ambitious future where the opportunities for innovation are limitless.

I think facial recognition technology will be at the center of storytelling — in a good and bad way. People will use their faces (and body language) to unlock devices, to browse the web and interact with software seamlessly. This will be extremely convenient for accessing centralized platforms or remembering passwords.

But it can also help verify identities and validate increasing aspects of our lives. People will use facial recognition tech as a source of their own credibility — it will likely be the authenticating factor for everything we do: signing in to social media, buying groceries, applying for jobs, and more. And since so much of our lives will rely on the presence of our face, it will be impossible to go through life without a digital presence, which presents a security risk for people, businesses and governments.

Using artificial intelligence and facial recognition tech to verify our identities will become a liability for law enforcement, espionage, identity theft and insurance fraud. Having photos of someone’s face will allow people to access data about their lives and personal history. It might make it easier to tell stories (what a helpful way to verify a source!), but it could also be a way for newsrooms and the communities they serve to be hacked or held hostage.

As we continue to find new uses for AI, it’s critical that we find a balance between innovation, security and civil liberties.